This month’s letter will be discussing your biomechanical hardware, so to speak. If you’ve been curious about what can cause things like Carpal Tunnel Syndrome and other nerve injuries involving the wrist and hands, the paper (take a deep breath if reading aloud) Pathophysiology of Nerve Compression Syndromes: Response of Peripheral Nerves to Loading has data to help you grasp that better. I’ll share what this review covers and insights that can help you position your body in a way that keeps your nerves talking to you like a friend.

Among the papers I’ve gone over for the monthly Ergo Life 101 newsletter, this title has earned its place as one of the top most wordy titles thus far.

Let’s dig in.

Keyboards and Nerve Tissue: Can we be friends?

To start, we owe a great thanks to David Rempel, M.D. as he has been involved in a large percentage of the foundational research needed to even begin to have conversations about the ergonomics of keyboards. He and about three other data-seekers have been holding up this research for more than 20 years. This paper in particular is a review of the information that was available at the time of writing about nerve compression and what postures may cause it and its effects, so we get a view of where we stand data-wise. Which is important, considering the place keyboards hold in the world today.

A greater number of people in the modern day (like you, dear reader) are using their keyboards more and more. Many of you might be on par with that of an Olympic athlete such as Simone Biles, 11-time Olympic gold medalist, in terms of your usage and training so to speak--on the tool of your trade. Biles trains roughly 6-7 hours a day, with rest days. I do not think it is far-fetched to say that the usage of keyboards day-to-day far exceeds that amount for many people. It’s a bit hard to pin that down with data though, given the variety in our usage of technology, it is hard to pin down population-level statistics for time spent at a keyboard.

While mechanical keyboards have been growing as a fantastically fun hobby that is a doorway to learning skills like soldering, PCB design, CAD design, programming and computer gaming, it is also a method to alleviate wrist/elbow injuries or prevent them to begin with.

The last few papers I’ve read have largely focused on how the shape and position of the keyboard can impact posture and the body.

This time around, our friend Dr. Rempel and colleagues, collected data on the structure of nerves, normal loading on nerves and how that loading contributes to health issues like Carpal Tunnel Syndrome.

While focusing on the function of nerves may seem like a stretch away from keyboard positioning, it presents a new angle to look at how we position ourselves for our Olympic-level work durations at our keyboards.

A Different Angle of Data

“Basic knowledge of the microanatomy of peripheral nerves and neurons and of their complex reactions to compression is essential to understanding, preventing, and treating nerve compression injuries.”

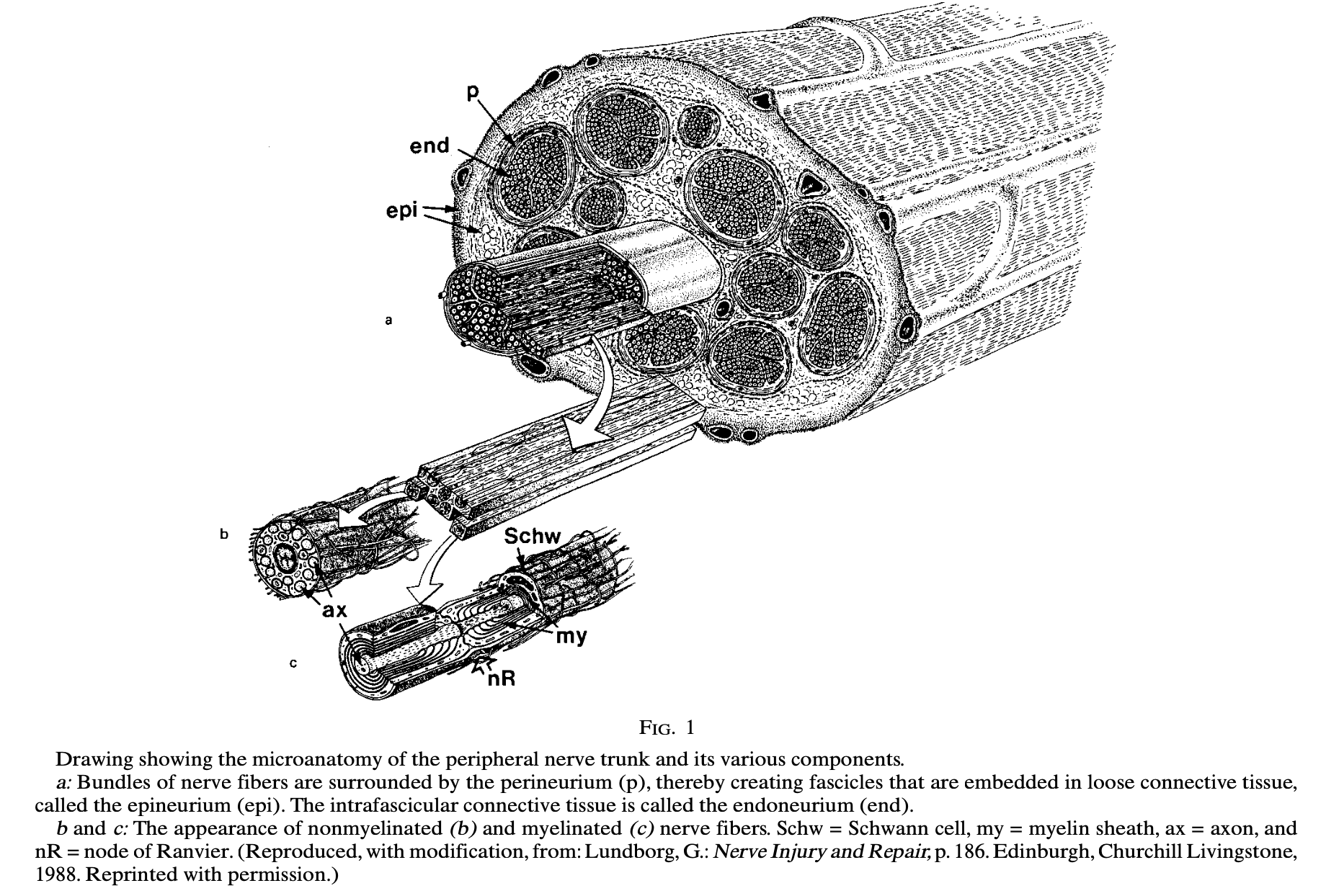

Before we talk about what loads on our nerves can cause problems, Dr. Rempel et al. take a moment in the review to discuss the anatomy and function of peripheral nerves (nerves located outside the brain and spinal column). If you’re not big into the microanatomy level of stuff, jump to the next section. Because it’s time to talk about the tiny yet critically important parts of us that keep us moving.

In perhaps an oversimplified explanation, the microanatomy of peripheral nerve trunks involve many smaller parts inside them that need to move together. When we bend our wrists or pinch something, we are compressing our nerves, so pressure levels change inside and around the nerves. For example, when you grip something cylindrical in shape or make a fist, you are increasing the pressure levels in and around your nerves. Gripping something is a form of load, as this paper refers to it.

“When tissues are subjected to load or pressure, they deform and pressure gradients are formed, redistributing the compressed tissue toward areas of lower pressure.”

Some of this will sound intense, but I promise it’s just a discussion of parts of a nerve. If it gets confusing, take a look at the picture below. Courtesy of the review.

Injury Created in 2 Hours? One Month of Change.

A highlight of note early on in the review is the strong focus on microvascular function-the small components in blood vessel walls. Blood passing through all your vessels is important, and the restriction of that passage is a problem.

For some of the data collected on what impact nerve compression has (effects in hours vs effects within days vs effects within weeks), animals were used to help us learn more about this. Some studies had created an artificial form of compression of the nerves to try and “induce acute or chronic compression.” Two things in particular stood out:

1 The induced nerve-compression in animals taught us that two hours “can initiate a process of nerve injury and repair and can cause structural tissue changes that persist for at least one month.” Which is a statement that honestly made me reconsider how much recovery time is needed for injuries. Two hours to cause at least one month of damage is an astounding level of rest time needed. I wonder if there are more injuries we sustain where the recovery time is underestimated?

2 I won’t go over it too much, as the relevance to keyboards is limited, but this paper does specifically look at vibrations as a form of load nerves can experience, and how this load can impact neuropathy (injury to nerves outside the brain and spinal cord). The prevalence of this in the review may be explained by the fact an early version of this paper was commissioned by the National Academy of Sciences and appears in Work-Related Musculoskeletal Disorders: Report, Workshop Summary, and Workshop Papers. The vibration of tools and other such things can cause nerve breakdown (failure of “myelin and interstitial and perineurial fibrosis.”) Tool vibration is different from keyboard usage, but both fall under the umbrella of occupational hazards to health and safety. It’s wonderful to see a focus on how this research can help many kinds of workers in different fields.

Peripheral nerve dysfunction which stems from microvascular function (or lack thereof) is the five-dollar concept of the day, as these two go hand-in-hand in creating issues with what loads our nerves cannot continue to endure.

Finger-Loading

Of particular relevance to those of you with extended--Olympic--hours spent at a keyboard is this section on finger loading Dr. Rempel et al discuss on page 1607. We make a big fuss about our switches, and rightly so. There’s good data to be had about that.

“Finger-loading (for example, pinching) also increases carpal tunnel pressure in normal subjects and in cadavera. In cadavera, the extraneural pressures in the carpal tunnel increased when the flexor tendons were loaded. Similarly, in healthy volunteers, the pressures increased during simulated holding and gripping tasks.”

All the time you spend choosing comfortable switches? Arguably time well spent.

While we’re still depending on cadavera (cadavers) for this data since it would irreparably damage a living person’s nerves to do the necessary biopsy, it’s still helpful information to augment the data we can gather from actual living folks.

Dr. Rempel et al. go on in the review to say that the mean extraneural pressure (pressure surrounding the nerve) increased when Seradge et al asked their subjects to hold a 10.5-centimeter cylinder and it increased more when subjects made a fist. They state 3 other papers also had similar findings. Repeatable! Repeatable results are exciting, giving us a window to more solid information.

These “findings that non-neutral joint positions and external load (for example, during pinch grip) can affect extraneural pressure, combining with the findings from the animal studies, can guide our understanding of the pathogenesis of nerve entrapment related to loading.” Knowledge about positioning and loading can guide our understanding about how problems like CTS arise.

Even more interesting is identifying that if a high pressure is kept up for a duration, the processes responsible for repair are likely to become overwhelmed, and cease to do what they need to, “leading to…loss of nerve function.” But the time that is needed to pass this limit has not yet been determined. In all likelihood, it probably varies person to person, but that’s just conjecture as no data (that I’ve found) supports that yet. I’ll update you when I find that!

It is strongly noted at the end of this segment in the writing that catching symptoms early on (defined as: discomfort experienced at night or only during activity) is crucial to save the greatest amount of the nerve function. After a certain point, “operative release” may be the only way and “there is no guarantee that nerve function will return completely.” The old adage ‘an ounce of prevention beats a pound of cure’ comes to mind. Or if you’re not used to the strange measurements of the States (I get it, I weigh my baking ingredients in grams!), perhaps an equivalent of 'a gram of prevention beats a kilogram of cure' works.

Changing things about your setup if you’re experiencing pain or tingling may be worth considering even when these symptoms feel slight.

Of Windows and Keyboards

Our keyboards are a bit like a window to the digital world. They allow us to communicate with words, coding, or images to name a few ways. Merely a few clicks and clacks to reach across the world to say hello.

It isn’t a matter of defining the human body through its limitations, but recognizing how we can better accommodate the abilities we have. Changing your switches or the position of your keyboard may be worth experimenting with.

I didn’t cover every last detail of the review as it is remarkably thorough, so if you’d like more (akin to a quick drink from a fire hydrant), here’s a link to where you can read the paper.

Disclaimer: Keebio is not affiliated with The Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery. Kayla is not a doctor. She's also not wearing a lab coat. She just thinks talking about ergo studies might get more ergo conversations happening, which might lead to more studies. Ya-ha-ha!

Member discussion